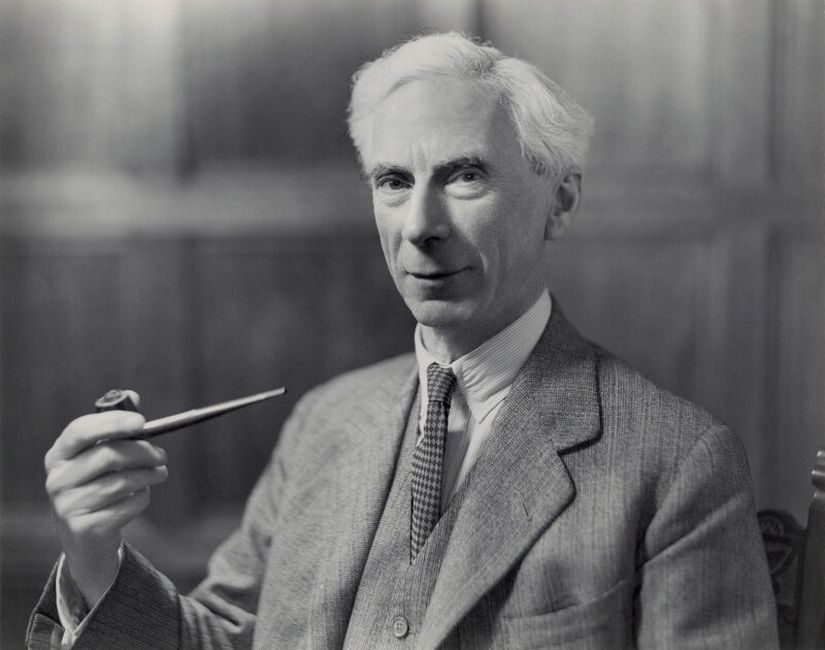

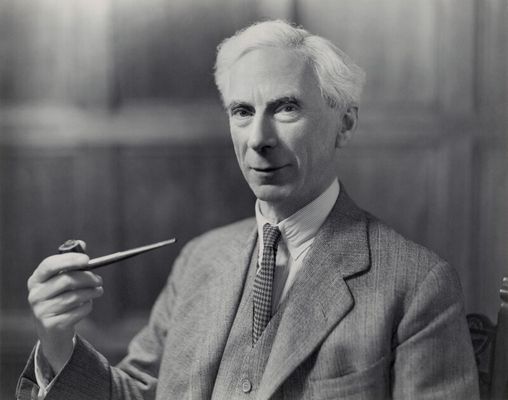

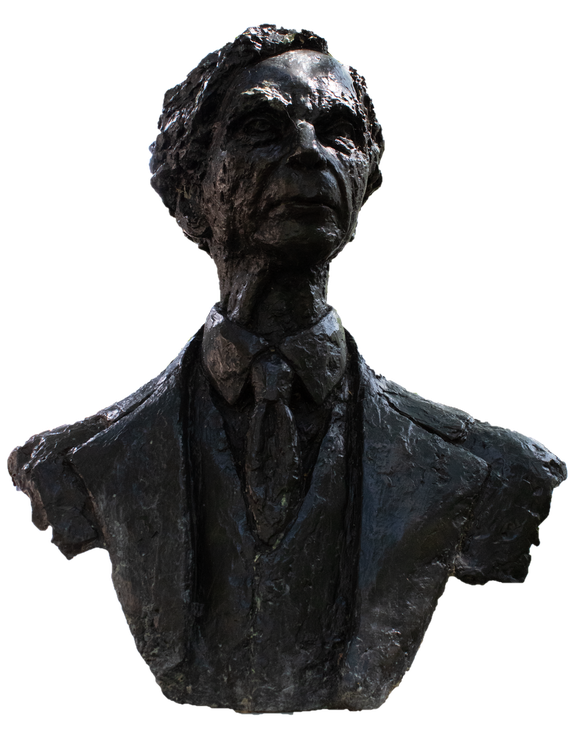

Bust of Bertrand Russell

Marcelle Quinton, 1980Bertrand Russell, 3rd Earl Russell is best known as a philosopher, mathematician and peace campaigner. He wrote more than 70 books, around 2000 articles and many letters to leaders across the world. He was an anti-war activist and was influential in many areas, including maths, computer science, philosophy and politics. In 1950 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.’

The Bertrand Russell bust is part of RePresenting Bloomsbury

Bertrand Russell, 3rd Earl Russell is best known as a philosopher, mathematician and peace campaigner. He wrote more than 70 books, around 2000 articles and many letters to leaders across the world. He was an anti-war activist and was influential in many areas, including maths, computer science, philosophy and politics. In 1950 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.’

The Bertrand Russell bust is part of RePresenting Bloomsbury

About Bertrand Russell

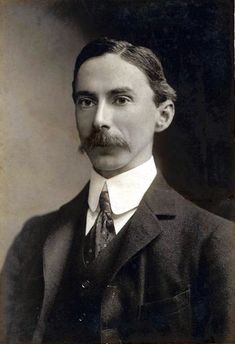

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872 to an aristocratic family closely related to the Dukes of Bedford, who own land in Bloomsbury. His parents died by the time he was four and he was brought up by his religious and forward-thinking grandmother, who taught Bertrand a sense of social justice. His grandfather was a Liberal politician who was Prime Minister twice.

From 1890 Bertrand studied mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. His work with A.N Whitehead, Principia Mathematica (1910), is seen as an important and influential work in the history of mathematics and philosophy. He lectured at Trinity from 1910 – 1916 when he was dismissed due to his public support of a conscientious objector to the First World War.

Bertrand Russell is known as a life-long pacifist. During the First World War he campaigned against conscription and the war. In 1918 his pacifist activities landed him in Brixton Prison for six months, prosecuted under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914. This would not be his last arrest. In 1961, aged 89, Bertrand was sentenced to seven days in prison for ‘inciting civil disobedience’ for organising mass protests against nuclear weapons. During the 1950s and 1960s he campaigned for the total ban of nuclear arms with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

In 1948 Bertrand delivered the inaugural lectures named after the BBC’s first Director-General Sir John Reith. Bertrand’s series of six lectures were called ‘Authority and the Individual’ and they explored the role of state control in a progressive society and the role of the individual in forming community.

Bertrand's complex views

He held changing views at various points in his life, sometimes with unresolved contradictions. Bertrand was an early supporter of women’s suffrage, standing for parliament in Wimbledon on behalf of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1907. Yet his relationships with women were complex. He married four times to active, feminist women, who (sometimes reluctantly) assumed the role of supportive wife and mother to his children. His commitment to women’s right to vote is not viewed as feminist, but because of his strong belief in the importance of democracy. He stated that women’s suffrage was “part of the democratic movement……..[which] made it impossible to find any logical answer to the demands of women.” (Russell, B. Marriage and Morals, 1929).

Changes in his ideas are present in other areas of his thinking. Early in his life he was a Liberal Imperialist, believing in the British Empire and the notion that colonisation would ‘civilise’ peoples. In a letter to Louis Couturat in 1900 he said, “…I would like to see all of Asia (including the Indies) belong to Russia, all of Africa to England, and all America to the United States. Then we could expect everywhere a durable peace and civilized government”. He later changed his mind. By 1910 his views on empire had shifted to anti-imperialism and he started to support the Indian independence movement. Between 1932 and 1939 he chaired the India League, working with his friend V.K Krishna Menon to actively campaign for Indian self-government and independence.

His views on sexuality and procreation were also complex. He was a vocal supporter of the Homosexual Law Reform Society which campaigned for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. He publicly presented his progressive ideas on open marriages, sex before marriage in ‘trial marriages’ and increased access to contraception and sex education. However, Bertrand was also an early supporter of eugenics, particularly around disability and class, which we find totally unacceptable today.

Bertrand’s comments on race, suggesting white supremacy, have also been rightly questioned and criticised, with some of his early work rewritten and reworded in the 1960s. He claimed that his writings of 1929 were not intended to be racist but understood they were ‘ambiguous’ and redacted them later. By 1951 he was a vocal supporter of racial equality and intermarriage.

Bertrand Russell’s ideas and writings spanned over 80 years and his views on society and politics changed and evolved over his long life. He wrote a large number of letters, articles and books but he is perhaps best known as a peace campaigner, advocate of social justice and supporter of Indian independence.

The bronze bust of Bertrand Russell was made by sculptor Marcelle Quinton in 1980. It was commissioned by the Bertrand Russell Memorial Committee chaired by Fenner Brockway, and unveiled by his former wife, Dora Russell.

Community Voices

We worked with Camden communities and artists to explore Bertrand Russell. Together they made artworks and sound pieces informed by his life and work. These are presented below.

Holborn Community Centre

Over the summer term 2023, artists Lottie McCarthy and Toby Tobias worked with an intergenerational group of people at Holborn Community Centre. They talked about the life and work of Bertrand Russell together and created new artworks in response.

Over a series of workshops the group explored Bertrand’s work and ideas, his influential thinking, essays and campaigns. They also explored Bertrand’s family life, class and privilege as well as his views on eugenics. The artists and participants shared research notes about Bertrand’s work and material from the Conway Hall archives as well as letters, diaries and manuscripts.

The group considered the meaning of public art and the act of memorialisation. They talked about how the statue of Bertrand was commissioned and the memorial committee behind its installation. During the workshops, and through the discussions, the participants crafted mini-sculptures using clay. The group wanted to reflect their own ideas about who, or what should be memorialised.

It was decided that the mini-sculptures should be ‘installed’ at the Bertrand Russell statue. They held a special “people’s committee” unveiling ceremony in Red Lion Square where objects, mini-sculptures and fabrics were added to the statue and its plinth. Some speeches were made:

‘The people's democratisation memorial to anti statues in Camden:

To all of those who have donated, many thanks for your donation of time and clay… All has gone well and you are invited to attend the unveiling of the memorial…now. No lords or ladies will preside over the ceremony and no one called Dora will unveil what was done. The ideas stemmed from people whose names will remain anonymous. They took up the matter with no lords or ladies and no appeal committees were constituted. No sirs knew the work of the sculptors. Nobody advised on the site, design, plinth, or arranged the installation. No sir’s or siresses will speak during the ceremony. And no honourable secretaries will have any part in this at all. The mayor will not be present. After the ceremony all donors are invited to a reception on this bench right here.’

People chose where and how to place their sculpture. Someone spoke, one played a recording of their mother playing the piano, and another played an excerpt of Bertrand’s speech giving advice to future generations.

One participant had a friend who knew Bertrand and claimed that he ‘had queer relationships and was also a shabby dresser’. So, the statue was adorned with a shabby suit and rainbow fabric to celebrate this. A pair of clay glasses were placed on the bust to represent Dora Russell, the second wife of Bertrand, who had unveiled Bertrand’s statue in 1980. A clay pigeon was placed on top of Bertrand as a nod to the bird poo that the bust consistently has.

The group returned after a week to see what had become of their mini-sculptures. Many had disappeared, either collected by passers-by, or disintegrated into small mounds of clay. One remained; Patricia Forrest, a friend of one of the participants who had devoted her life to community and charity work. Patricia was in perfect condition apart from the Bible that she had been holding, which had been knocked off. The group felt ‘it was as if Bertrand Russell decided Patricia was worthy of staying by his side….as long as the Bible didn’t’.

Voices of Holborn Community Association

At the beginning of the sound clip (left), you can hear the introduction to the event held at the Bertrand Russell bust by Holborn Community Centre. Then participants, Jill and Caroline talk about their thoughts on statues, Bertrand Russell, and the workshops.

Conway Hall

Across one weekend in the summer of 2023 artists Lottie McCarthy and Toby Tobias worked with members of Conway Hall audiences. Bertrand Russell had very close connections to Conway Hall, who hold some papers relating to him and have a room named after him. Together they explored Bertrand Russell’s BBC Reith Lectures of 1948, entitled ‘Authority and the Individual’.

Using research, cut-up copies of poems, free-writing, texts from the archives at Conway Hall and printed transcripts of Bertrand’s writing the participants made new creative responses to his works and philosophies. The group explored Bertrand’s ideas on family life, class, eugenics and politics. They also explored his privilege. Through discussion the group began to re-create or re-imagine their own Reith Lectures. Each performed their lecture to the group at Conway Hall.

Participants collaborated to create a cut-up poem, performed in three sections by three participants in the main theatre at Conway Hall. A solo poem was also performed on the balcony, using the different levels (ground, trap-door, stage, balcony) to signify ‘hierarchy’, ‘pedestaling’, and ‘unburying’, with different performers moving to higher and lower ground. Another participant performed a semi-improvised piece drawing on the memory of her grandmother who had brought her to Conway Hall as a young child to hear Bertrand Russell speak.

Voices of Conway Hall

You can hear two people from these workshops in this sound clip (left), Julianna and Syed, talk about what drew them to the workshops, what they found out about Bertrand Russell, and their thoughts on statues and public art.

Supporters